Swiss researchers have developed a new battery prototype that could potentially store more energy, while maintaining high levels of safety and reliability.

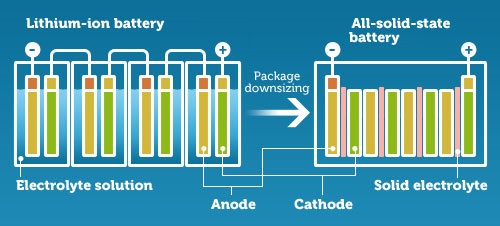

The technology, known as ‘all-solid state,’ is based on sodium, a cheap alternative to the lithium that sits inside most modern batteries. When a battery charges, ions leave the cathode and move to the anode. Most lithium-ion batteries use a graphite anode to prevent the formation of lithium dendrites – branching growths that can cause short circuits and fires.

But, using a metallic anode would increase the amount of energy that could be stored, so that’s exactly what researchers from Empa, Switzerland’s federal laboratory for materials science and technology, and the University of Geneva have done.

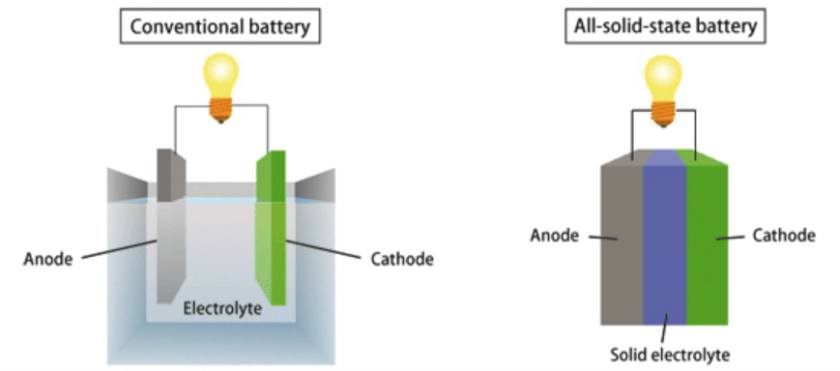

Their battery uses a solid electrolyte instead of a liquid, which allows them to use a metal anode without risking the formation of dendrites.

The main benefits are batteries that are smaller, higher-capacity and cheaper than current liquid-based lithium-ion batteries. In 2014, Sakti3 announced it was approaching a point where it could produce a battery with twice the density of current batteries at a fifth of the cost. They’re also non-flammable and, in theory, could last longer and charge faster.

As the Samsung Galaxy Note 7 proved, the cost of getting a battery design wrong can be huge. Current lithium-ion batteries are flammable and they also create a lot of heat, which in electric cars means lots of extra gear to contain and dissipate it. An electric car with a solid-state battery could remove all the cooling elements in favour of a larger battery, and therefore longer range, or reduce the size of the battery while retaining the same range and cutting the cost.

Current batteries are also notorious for having short lifespans. Constant charging and discharging slowly erodes the performance of the battery, which is why a two-year-old iPhone often struggles to get through a whole day of use on one charge.

According to Ilika, a developer of solid-state batteries for Internet of Things devices, they could increase ‘cycle life’ from two years to 10 years. A Wall Street Journal report suggested this could result in greater potential for product recycling after being used in the vehicle, such as in homes or commercial energy storage.

“But we still had to find a suitable solid ionic conductor that, as well as being non-toxic, was chemically and thermally stable, and that would allow the sodium to move easily between the anode and the cathode,” explained Hans Hagemann, professor of physical chemistry at Geneva.

They settled on a close-borane, a boron-based conductor that enabled to sodium ions to circulate freely within the battery. Because it’s an inorganic conductor, it removes the risk of the battery catching fire while recharging, according to the researchers.

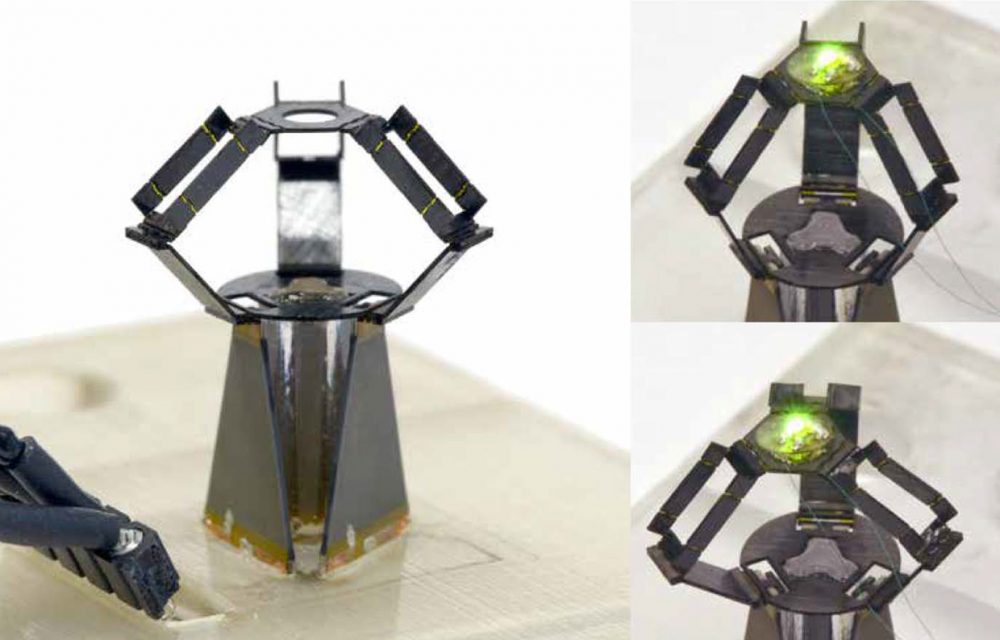

“The difficulty was establishing close contact between the battery’s three layers: the anode, consisting of solid metallic sodium; the cathode, a mixed sodium chromium oxide; and the electrolyte, the closo-borane,” said researcher Leo Duchane.

To solve this problem, they dissolved part of the electrolyte in a solvent, before adding sodium chromium oxide powder. After the solvent had evaporated, they stacked the cathde powder composite with the electrolyte and anode and compressed the layers to form the battery.

When testing the battery, they found that could withstand three volts – a level above solid electrolytes which have been previously studied, according to Arndt Remhof, the project leader. They also tested it over 250 charge and discharge cycles, and found that 85% of the energy capacity was still functional. ““But it needs 1,200 cycles before the battery can be put on the market,” say the researchers. “In addition, we still have to test the battery at room temperature so we can confirm whether or not dendrites form, while increasing the voltage even more. Our experiments are still ongoing.”